Abstraction is not a trick developers use to hide work. It is not a shortcut PMs rely on to ship faster. And it is not something QA should blindly accept or blindly fight.

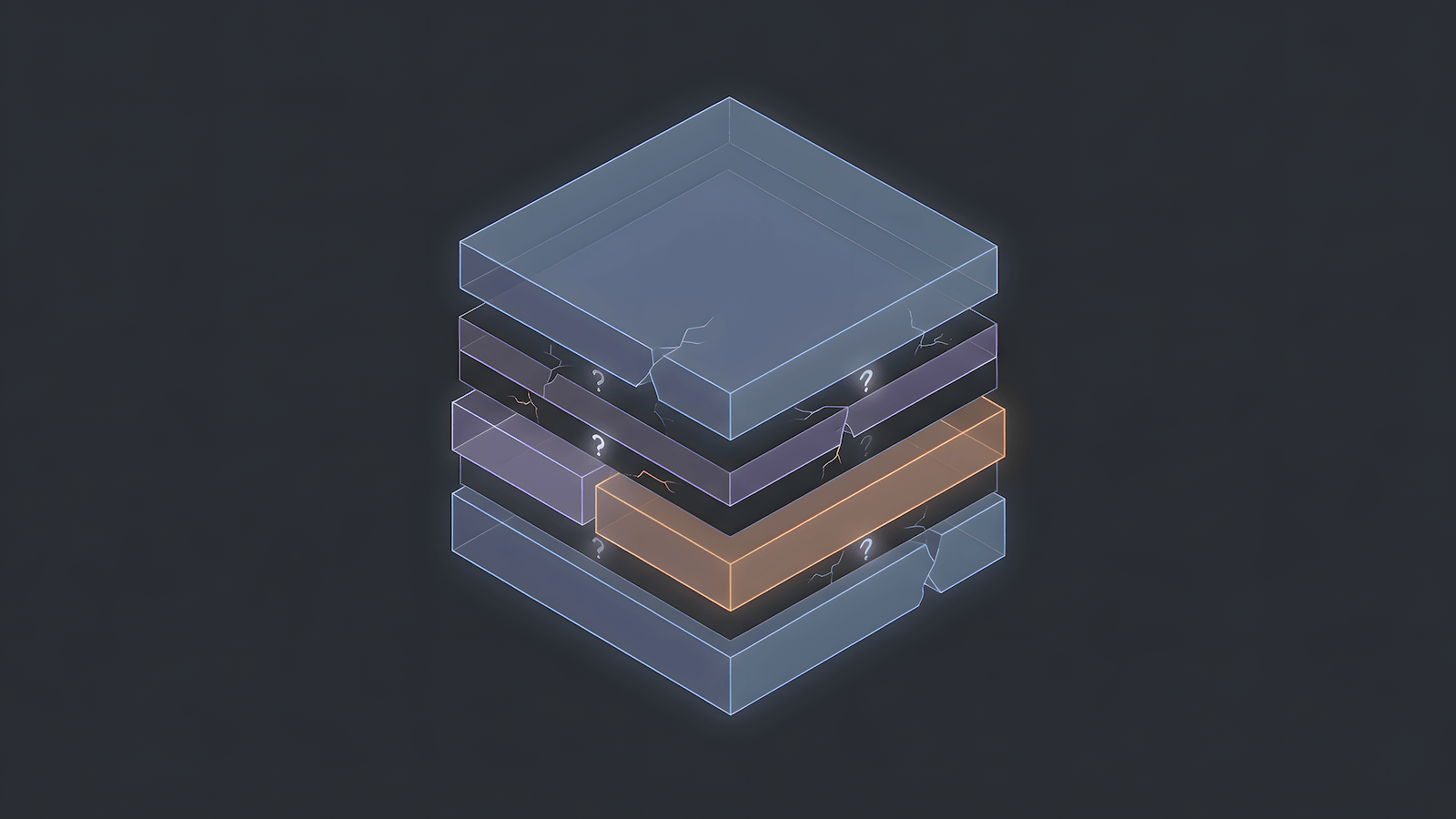

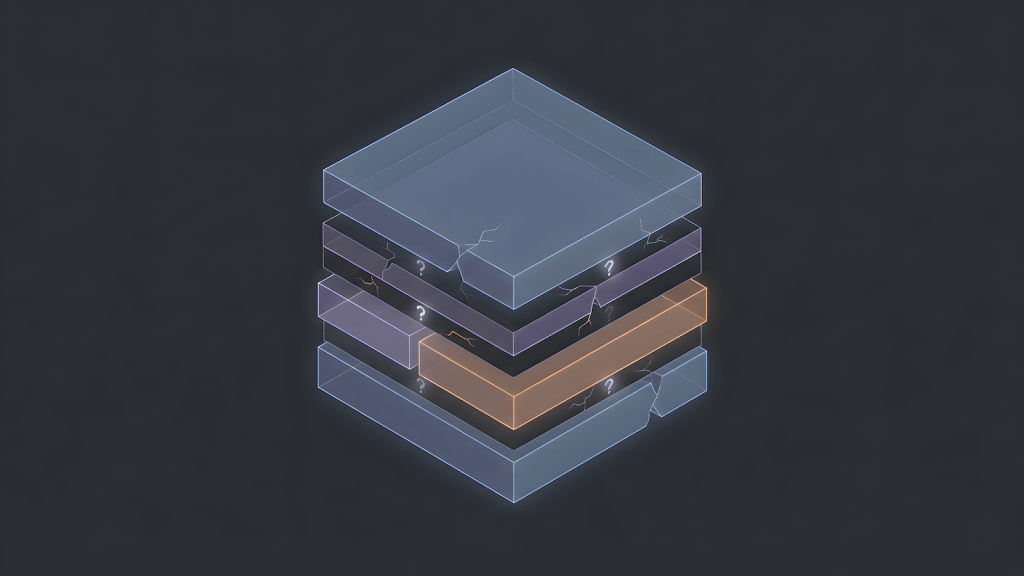

Abstraction is a tool. It compresses complexity so teams can move forward. That compression is necessary. But compression always discards detail, and discarded detail is where risk hides. The real problem is not abstraction itself. The problem is when abstraction becomes invisible.

That is where QA actually belongs.

Why Abstraction Exists in Real Software Teams

Every functioning software team relies on abstraction, whether they acknowledge it or not. User stories replace raw requirements. Acceptance criteria replace full specifications. APIs replace direct data access. Components replace monoliths.

None of this is wrong. It is the only way complex systems get built.

Abstraction allows teams to reduce cognitive load so work can proceed, parallelize effort across roles, and avoid re-solving the same problems repeatedly. But abstraction does not eliminate complexity. It relocates it.

When teams forget where that complexity went, they stop validating behavior and start validating belief.

Where Abstraction Quietly Breaks Testability

Abstraction usually fails silently. Not through obvious defects, but through gaps that appear only when someone tries to verify real behavior.

A ticket looks clean on paper. The user story is approved. The acceptance criteria are met. Development finishes on time. Then QA begins testing and immediately encounters ambiguity.

Edge cases were assumed away. Error states were labeled as “handled elsewhere.” Dependencies were implied rather than stated. Nothing in the ticket is technically incorrect, but the abstraction removed just enough context to make correctness unverifiable.

This is not QA being difficult. This is QA restoring specificity so the system can actually be tested.

This is also why QA already relies on a fragmentation approach to QA testing: breaking complex systems into testable surfaces, isolating failure points, and exposing causal boundaries. Abstraction becomes dangerous only when those surfaces collapse into assumptions instead of behaviors.

Fragmentation and Abstraction Are Not the Same Thing

During grooming and sprint planning, work is intentionally fragmented. Smaller tickets are easier to estimate, easier to build, and easier to review. This is healthy.

Problems arise when fragmentation and abstraction blur together.

As tickets get smaller, intent often gets simplified. Responsibility shifts implicitly instead of explicitly. By the time work reaches development, the abstraction is no longer just smaller. It is thinner.

QA’s role here is not to challenge the breakdown itself. It is to verify that the abstraction still represents real behavior and that the assumptions removed during fragmentation are safe to remove.

When abstraction becomes too thin, communication loss follows.

How Abstraction Moves Risk Across System Layers

Another common failure mode appears when abstraction shifts responsibility without making that shift explicit.

A typical example is storing raw data in the backend while delegating filtering, sorting, or validation to the frontend. The acceptance criteria pass. The UI behaves correctly. The ticket closes.

But abstraction has moved correctness elsewhere.

Now QA has to think beyond the UI. What happens when multiple clients consume the same endpoint? What happens when data volume grows? What happens when frontend and backend assumptions diverge?

No one made a bad decision. But abstraction changed where failures will surface, and QA is often the first role forced to confront that shift.

QA Exists to Validate Fit, Not to “Break” Software

The idea that QA exists to “break things” is lazy thinking. In a more funny way, QA is indeed the “breaker of things”, the “stopper of sprints”, the “gatherer of developer’s tears”, the “bane of PMs”, the “lone wolf” and the “one the stands alone in the face of adversity”.

In strong teams, QA does not exist to embarrass developers or block releases. QA exists to validate whether the abstraction still holds when the system is exercised under real conditions, not ideal ones.

That means asking questions that abstraction tends to hide. What assumptions are we relying on? What behavior is no longer visible? Where will this fail when the system is stressed, reused, or extended?

When teams understand this, the QA vs dev narrative collapses. Abstraction becomes a shared design responsibility instead of something one role has to defend.

How Blame Enters and How Healthy Teams Avoid It

Blame shows up when abstraction is treated as a personal failure.

PMs become defensive. Developers feel attacked. QA gets sidelined. Meetings devolve into role-versus-role debates instead of system discussions.

Healthy teams do the opposite. They treat abstraction as collective responsibility. PMs clarify intent when gaps surface. Developers expose assumptions instead of protecting them. QA frames findings in terms of system impact, not fault.

Bugs stop being personal and start being structural.

Abstraction as a Core QA Skill

Once QA understands abstraction, the job changes.

Testing stops being about checking outcomes and starts being about tracking where complexity lives. The work shifts from asking whether something is broken to identifying which assumption will fail first.

That is not theoretical QA. That is how teams prevent late surprises, uncontrolled technical debt, and systems that collapse the moment change is introduced.

The Actual Point

Abstraction is unavoidable. Fragmentation is necessary. Complexity never disappears. It only moves.

QA exists to track where it moved and whether the team still understands it.

Not to slow delivery.

Not to fight other roles.

But to make sure the system behaves the way everyone believes it does.

That is not adversarial.

That is professional.